The legal reality is straightforward: teachers are required by law to report suspected child abuse or neglect when they have reasonable cause to believe it may be occurring, and failure to do so can result in criminal charges, civil liability, and serious professional consequences.

Mandatory reporting is not a guideline, a recommendation, or something that can be delegated to a supervisor. It is a personal legal duty tied to the teaching role itself.

Misunderstanding where that duty begins and ends is one of the most common reasons educators face legal trouble later.

Why Mandatory Reporting Laws Exist

Mandatory reporting laws were created to address a simple reality: children often cannot protect themselves or report harm safely. Teachers are placed in a legally significant position because they see students regularly, observe patterns over time, and may notice signs that others do not.

At the federal level, child protection frameworks are supported by the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act, which requires states to maintain reporting systems as a condition of federal funding.

Oversight and guidance come through agencies such as the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, but the actual reporting rules, deadlines, and penalties are created and enforced by individual states.

While the details vary, every U.S. state and the District of Columbia includes teachers as mandatory reporters.

Who Is Legally Considered a Mandatory Reporter in Schools

In most states, the category of “mandatory reporter” in education is broader than many teachers assume. It almost always includes classroom teachers, but frequently extends to anyone employed by or working on behalf of a school who has contact with students.

This typically covers licensed teachers, special education staff, administrators, school counselors, psychologists, coaches, paraprofessionals, and substitute teachers. In some states, even volunteers or contracted service providers fall under mandatory reporting statutes if they work directly with children.

The obligation comes from the role, not from seniority or job title. A first-year teacher and a veteran administrator carry the same reporting duty under the law.

School Roles Commonly Covered by Mandatory Reporting Laws

School Role

Mandatory Reporter in Most States

Classroom teacher

Yes

Special education staff

Yes

School administrators

Yes

Coaches and advisors

Yes

Substitute teachers

Usually

Volunteers

Varies by state

What Teachers Are Required to Report

Mandatory reporting laws require teachers to report suspected abuse or neglect. They do not require certainty, proof, or confirmation. The law deliberately sets a low threshold because waiting for certainty can allow harm to continue.

Most state laws require reporting of physical abuse, sexual abuse, sexual exploitation, and neglect. Many states also include emotional or psychological abuse and exposure to domestic violence when it affects a child’s safety or educational access.

Importantly, the duty applies regardless of where the abuse occurred. Harm that happens outside of school, during weekends, or years earlier may still trigger a reporting obligation if it comes to light through the teacher’s role.

Understanding “Reasonable Cause” or “Reasonable Suspicion”

Reasonable suspicion is the legal standard that triggers the duty to report, and it is frequently misunderstood.

It does not require medical evidence, visible injuries, or a detailed disclosure. It means that, based on professional observation and experience, something appears inconsistent with a child’s safety or well-being.

Teachers are expected to rely on indicators such as unexplained injuries, repeated concerning behaviors, sudden emotional changes, age-inappropriate sexual knowledge, or statements made by the child or others that suggest harm.

The law explicitly states that teachers are not investigators. Determining whether abuse actually occurred is the responsibility of child protective services or law enforcement, not the educator.

How Reasonable Suspicion Is Applied in Practice

Situation Observed

Reporting Duty Triggered

Direct disclosure by a child

Yes

Pattern of unexplained injuries

Yes

Sudden extreme behavior changes

Often

Implausible explanations for harm

Often

Rumors without supporting indicators

Usually no

How and When Teachers Must Make a Report

View this post on Instagram

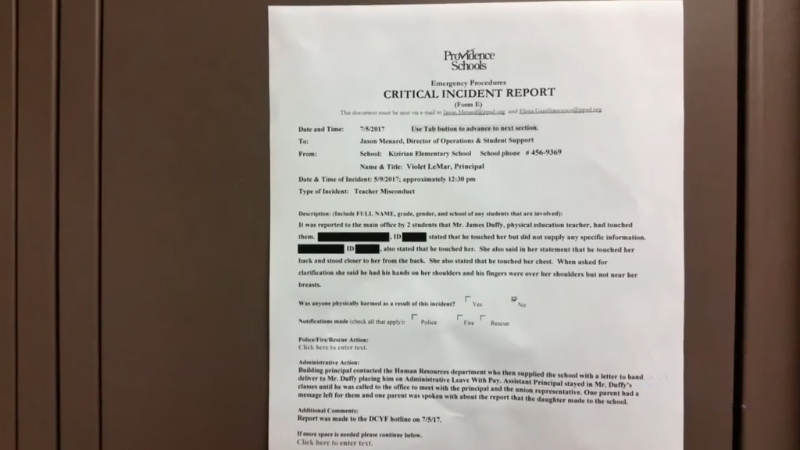

Once reasonable suspicion exists, reporting must happen quickly. Most states require reports to be made immediately or within a specific timeframe, commonly within 24 hours.

Delaying a report to gather more information or wait for administrative direction can itself be a violation.

Reports are typically made directly to child protective services, a state child abuse hotline, or local law enforcement. In many states, teachers must make the report personally.

Informing a principal, counselor, or administrator does not satisfy the legal duty unless the teacher also contacts the appropriate authority.

Some states require an initial oral report followed by a written report within a defined number of days.

Typical Mandatory Reporting Process

Stage

Legal Expectation

Suspicion arises

Duty to report begins

Initial report

Immediate or within 24 hours

Reporting agency

CPS or law enforcement

Written follow-up

Required in some states

Confidentiality and Legal Protections for Teachers

Mandatory reporting laws include strong protections for teachers who report in good faith. These protections are designed to encourage reporting without fear of retaliation or legal exposure.

In most states, teachers who report honestly based on reasonable suspicion are immune from civil and criminal liability, even if the report is later found to be unsubstantiated.

Their identity is generally kept confidential and is not disclosed to the accused except in limited legal circumstances.

Good faith does not mean the report must be correct. It means the report was made honestly and without malicious intent.

Penalties for Failure to Report

Failure to report suspected abuse is treated seriously by state legislatures and courts. Penalties vary by state but can be severe, especially if continued harm occurs after a failure to report.

Consequences may include criminal charges, usually classified as misdemeanors but sometimes elevated to felonies in aggravated cases. Fines, probation, or jail time may apply.

Civil lawsuits are also possible if a child is harmed further because a report was not made.

Professional consequences are often just as damaging. Teachers may face disciplinary action, suspension, or permanent loss of licensure, even if criminal charges are not pursued.

Consequences of Failing to Report

Type of Consequence

Possible Impact

Criminal penalties

Fines, probation, jail

Civil liability

Lawsuits for damages

Professional discipline

License suspension or revocation

Employment action

Termination

Career impact

Long-term reputational harm

False Reporting and Teacher Concerns

Teachers often worry about being punished for reporting something that turns out not to be abuse. In practice, this concern is largely misplaced.

Penalties for false reporting typically apply only when a report is knowingly false and made with malicious intent, such as retaliation or harassment. Reports made honestly, even if incorrect, are protected.

Courts and child welfare agencies consistently treat failure to report as a greater risk than overreporting when reports are made in good faith.

School Policies Versus State Law

School districts often have internal reporting procedures that require notifying administrators. While these procedures may be appropriate for coordination, they do not override state law.

Teachers remain personally responsible for ensuring that a report reaches the legally designated authority. Administrators cannot block, delay, or discourage reporting, and reliance on internal channels alone has repeatedly failed as a legal defense in court cases.

Common Misunderstandings About Reporting Duties

Belief

Legal Reality

Telling the principal is enough

Often not

Certainty is required

No

Abuse must occur at school

No

Another staff member will report

Still must report

Child asks for secrecy

Reporting still required

State-by-State Differences Teachers Must Know

While core principles are consistent nationwide, states differ in important details. These include reporting deadlines, whether emotional abuse is included, which agencies receive reports, and the severity of penalties for noncompliance.

Teachers are expected to know the law in the state where they work. Assuming that rules are the same everywhere is a common and costly mistake.

Final Perspective

@teachersoffdutypodcast Proud Mandated Reporter Hear the FULL episode at the link in our bio #teacherlife #teachertalk #teacherproblems ♬ original sound – Teachers Off Duty Podcast

Mandatory reporting laws place teachers in a legally defined role that goes beyond instruction and classroom management. The obligation to report suspected child abuse is personal, immediate, and enforceable.

It does not depend on certainty, administrative approval, or the potential discomfort of making the report.

Teachers who understand these laws clearly tend to act promptly and within legal boundaries, protecting both students and themselves. Teachers who hesitate or misunderstand the scope of their duty often do so with good intentions, but intention does not negate liability.